- This event has passed.

Sebastian Wolf

How does topography evolve during growth and decay of a mountain belt – inferences from coupled tectonic-surface process models

It has been a long-standing problem how mountain belts gain and loose topography during their tectonically active growth and inactive decay phase. It is widely recognized that mountain belt topography is generated by crustal shortening, and lowered by river bedrock erosion, linking climate to tectonics. However, it remains enigmatic how to reconcile high erosion rates in active orogens as observed in Taiwan or New Zealand, with long term survival of topography for 100s of Myrs as observed for example

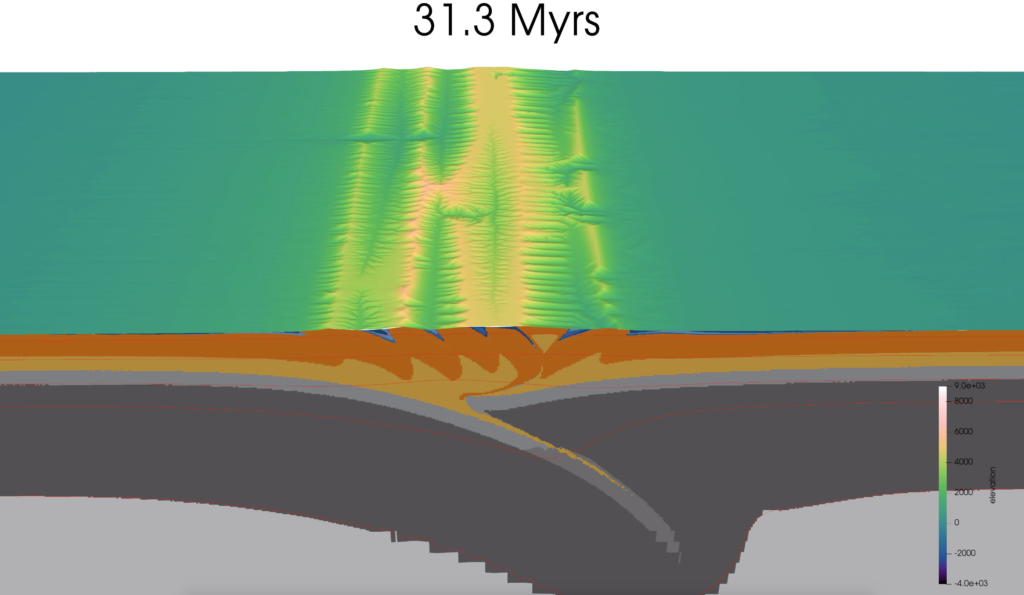

in the Uralides and Appalachians. Here we use for the first time a tight coupling between a landscape evolution model (FastScape) with an upper mantle scale tectonic (thermo-mechanical) model to investigate the different stages of mountain belt growth and decay. Using two end-member models, we demonstrate that growing orogens with high erosive power remain small (<200 km), reach steady state between tectonic in- and erosional material eff-flux, and are characterized by transverse valleys. Contrarily, mountain belts with medium to low erosive power will not reach growth steady state, grow wide, and are characterized by longitudinal rivers deflected by active thrusting. However, during growth both types of orogens reach the same height, controlled by rheology and independent of surface process efficiency. Erosional efficiency controls orogenic decay, which is counteracted by regional isostatic rebound. Rheological control of mountain height implies that there is a natural upper limit for the steepness index of rivers on Earth. To compare model results to various natural examples, we quantify the degree of longitudinal flow of modeled rivers with river ³longitudinality² in several active or recently active orogens on Earth. Application of the river ³longitudinality index² gives information whether (parts of) an orogen is or was at steady state during orogenic growth.